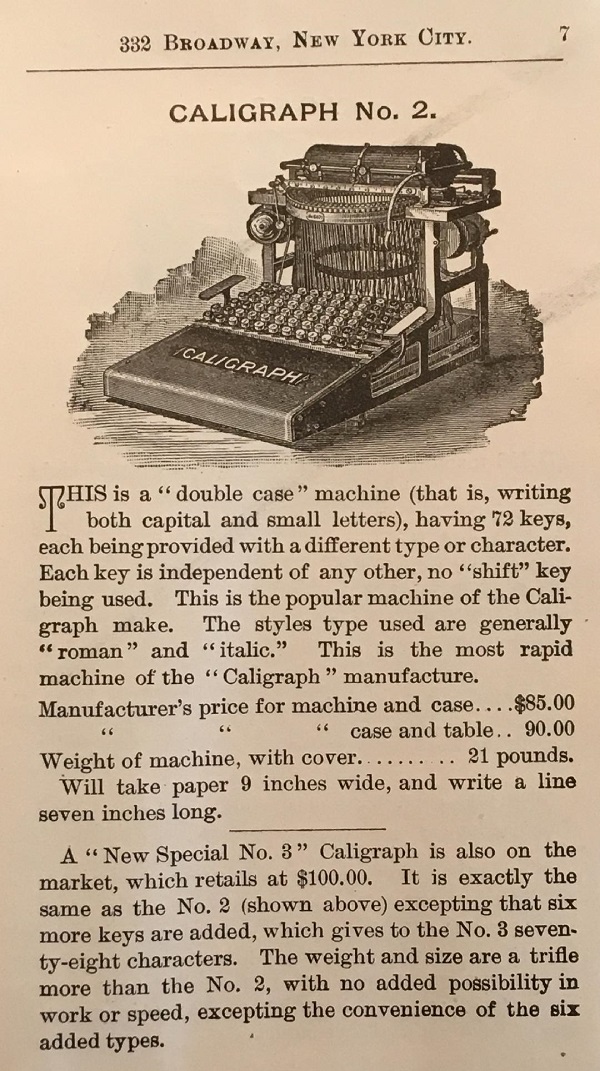

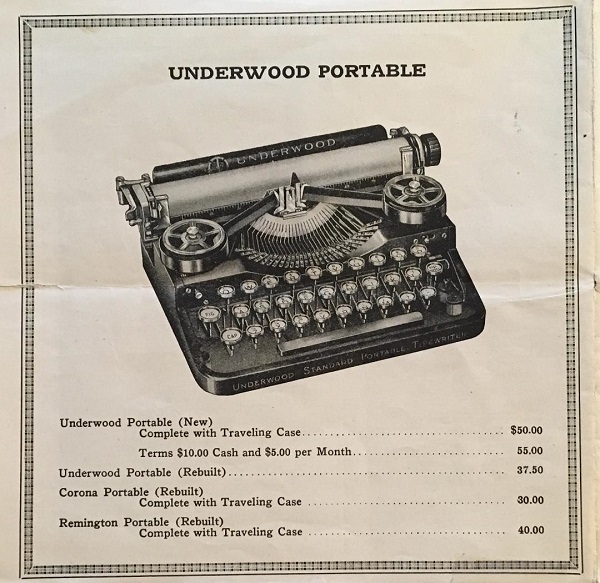

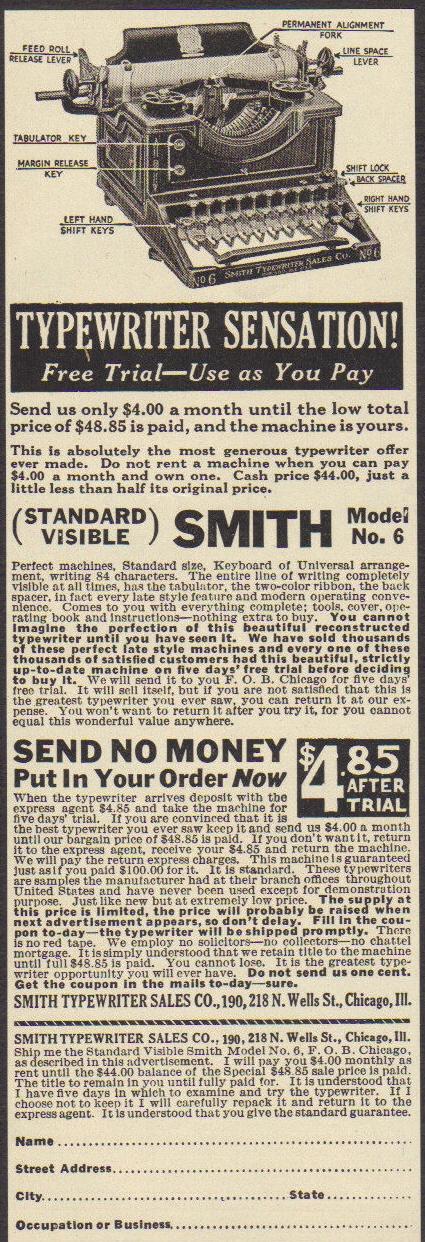

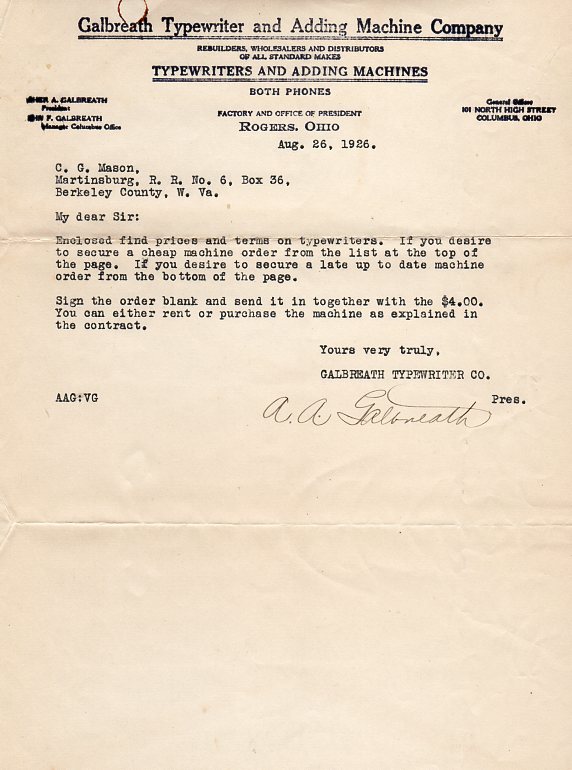

The typewriter above, a Smith Visible No. 6, is significant as a discovery in a number of ways – to historians, to collectors and in particular to those interested in the typewriter rebuilding industry and how it operated. Explaining what we are looking at is necessary to show its significance, so a couple of short histories are required.

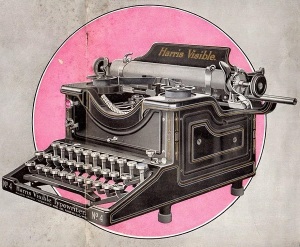

First, it’s obvious by this machine’s presence on this blog that it has been rebuilt. The history of the design is as follows: The machine was originally designed by DeWitt C. Harris for sale by Sears, Roebuck and Company as the Harris Visible. The first model to actually reach the market was the No. 4, and in fact only a few variances ever occurred on this model for roughly ten years.

(Above, Harris Visible No. 4 from Sears, Roebuck trade catalog circa 1913.)

The Harris proved to be a minor success in an already crowded industry and by the start of 1916 was selling independently from Sears as the Rex Visible; a new company, Rex Typewriter, was formed with new capital and carried forward. Sears still sold the machine through about 1920, always labeled as the Harris Visible. Sears advertised in 1913 that it had over 1000 Harris Visible machines in operation in its own gigantic Chicago offices.

The design became more or less obsolete over the years and by the start of the 1920’s the company set to work on a new, different four-bank machine called the Demountable. It was in 1922 that Rex, itself essentially bankrupt, was sold at Sheriff’s auction. The new buyers were, however, the old owners – and the company picked back up with the new name Demountable Typewriter Co. and began to market the wholly new machine. Keep the year 1922 in mind – it’s important.

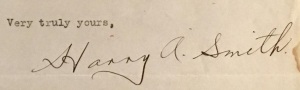

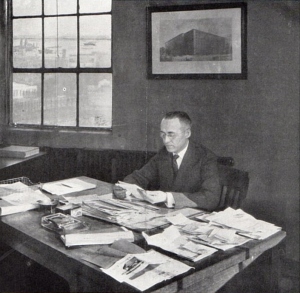

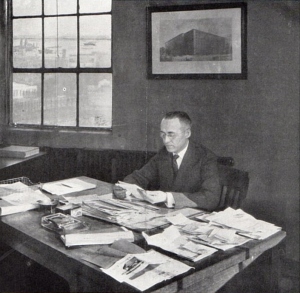

HARRY A. SMITH

Harry A. Smith (seen above near the end of his life) entered the typewriter rebuilding business in 1911, forming his own company in Chicago under his own name to rebuild typewriters. Smith knew how the business machine world worked, having been associated with the adding machine business for years. Rebuilt typewriters were becoming a very hot topic, even if the profit for such a business was marginal.

Smith’s business took off quickly, and he sold machines across the United States and around the world. Smith’s advertising was not unlike that of other firms of the day, and this got his company (and a number of others) in trouble with the Federal Trade Commission in 1917 when citations were issued for advertising of rebuilt typewriters without explicitly stating that they had been rebuilt.

Collectors today will note that Harry A. Smith was known also for something else that has, until now, been considered “off” – that is, the rebranding of machines with his own name instead of that of the original maker of the typewriter. This is exemplified by the photo below, showing two Victor typewriters.

On the right we see an original condition Victor Standard No. 3. It sits on its original shipping crate. On the left however is what was a Victor Standard No. 2, but which has been rebuilt by Harry A. Smith and which is now labeled as a Smith Visible No. 4. The name “Victor” has been chiseled off the side of the shipping crate on which the machine sits and Harry A. Smith stickers adorn the top of the crate.

Because early collectors 30 years ago or more began finding random and usually “off brand” machines relabled this way they assumed that Smith was buying up the stock of closed down companies. This is clearly not the case, though because Victor kept right on in business for years after these machines seen above were sold. The same phenomenon also exists with Harris / Rex machines as well. What was probably happening instead was Smith was acquiring machines which the original makers didn’t want their names on, or acquiring machines which had been recalled, or else acquiring machines when a model was closed out and the original maker had a policy of not allowing rebuilt machines out with its original name on them.

Smith was entangled with the FTC in 1917, but after this his company continued to relabel machines with his own name off and on until 1922. The last known model that Smith did this to was in fact the No. 6 you see at the top of this article.

HARRY A. SMITH No. 6 IN TWO VERSIONS

It is clear to us that Harry A. Smith sold relabeled Harris/Rex machines twice; once in 1917 and once in 1922. The origins of these stocks of machines are quite different.

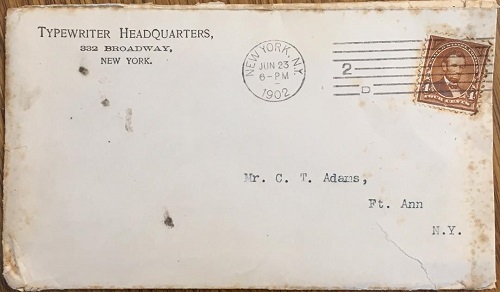

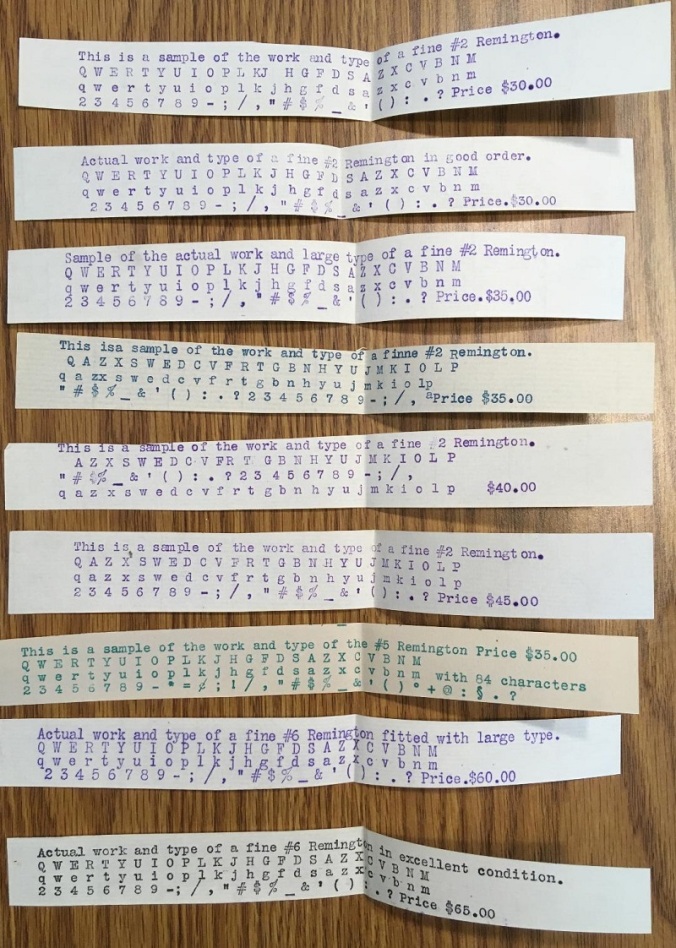

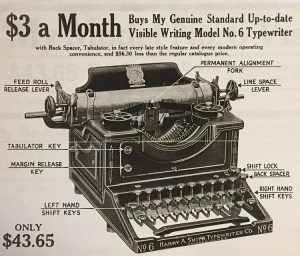

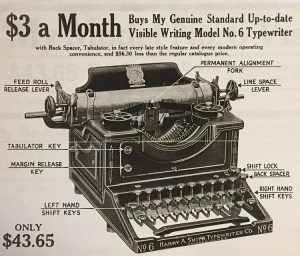

The illustration above, courtesy Peter Weil, is taken from a mailer that Harry A. Smith sent out as a response to an “act now!” coupon from a magazine. This 1917 flyer shows the first incarnation of the Harris/Rex as a Harry A. Smith No. 6. These machines, which in other ads Smith said he had a thousand of, are most likely the machines out of Sears’ Chicago offices, rebuilt and resold to the public.

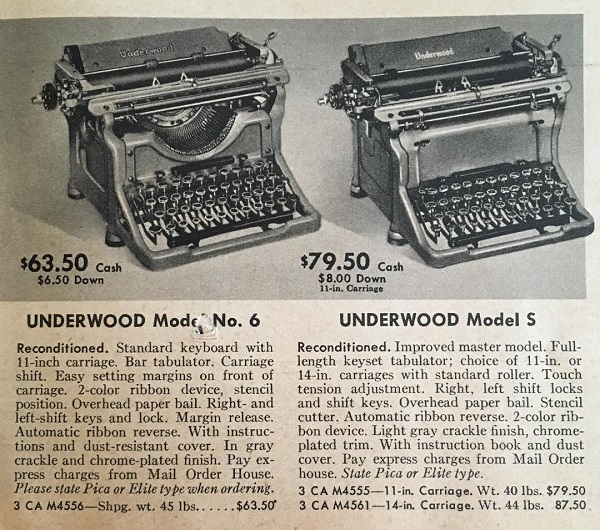

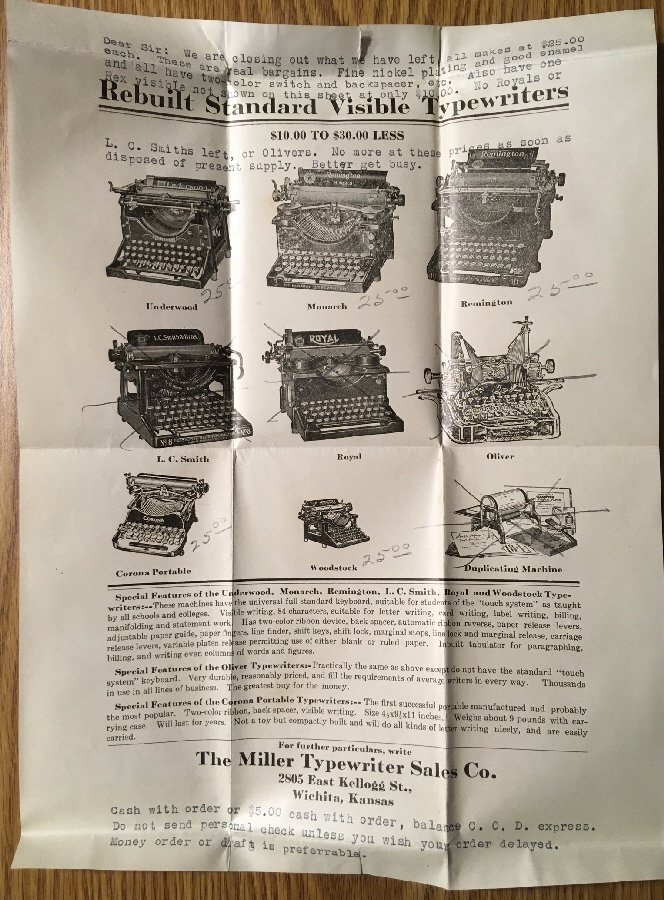

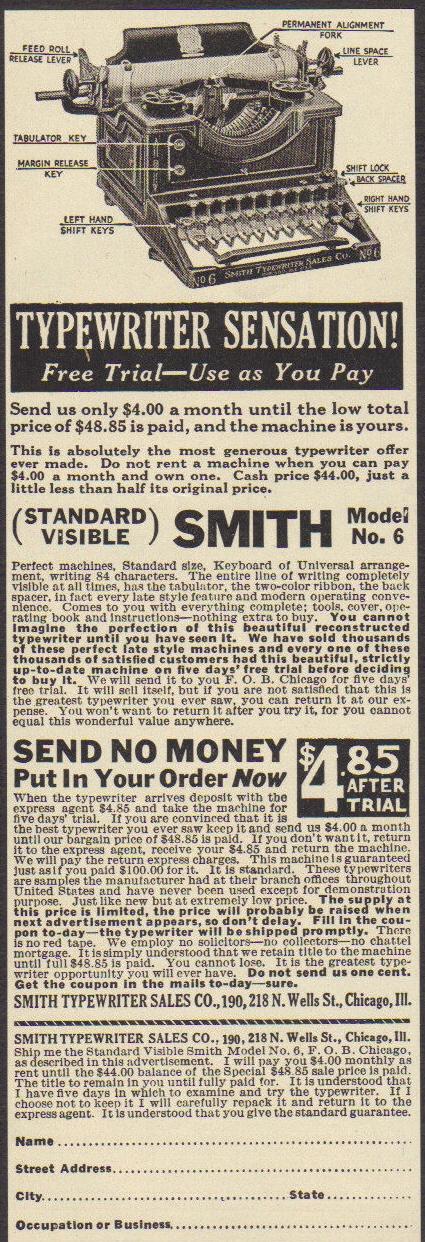

Above we see the 1922 ad in my collection for more or less the same machine, but several years later in a new offering. Note that the company name change to “Smith Typewriter Sales” has occurred; this happened in 1920 when Smith sold the rebuilding business and attempted to take the Harry A. Smith Typewriter Co. into the manufacture of new typewriters. That attempt failed in 1921, and eventually after some time Smith came back to his old company.

Smith Visible No. 6 and Observations

The recently acquired example of Smith Visible No. 6 (serial 11067) is the earliest variant of Rex Visible No. 4, with the ribbon selector present as buttons or keys on the sides of the machine. As stated clearly in the ad for the machine, the stock of this second known sale in 1922 consisted of samples from the Rex dealers around the country. At this time, the company was in the midst of another self-reinvention as Demountable, and as such these machines were surplus to demands as there was no intention to continue manufacture of this design in the future.

It seems clear that the Federal Trade Commission never cited Smith or his companies for rebranding machines; the only offenses were essentially false advertising. It stands to reason then that this practice, while unusual, was not considered illegal; knowing the story of this particular No. 6 helps fill us understand just what might have been happening each time Smith (chose to, was allowed to, was asked to) relabel machines with his own name.

Of further interest to collectors might be the fact that this Rex rebranding and a nearly simultaneous rebranding of another standard machine, the Stearns, in 1922 constitute the final examples of this practice for Smith’s company. Following this the company began work exclusively as a rebuilder for L. C. Smith & Bros. and dropped all trade in any other brands of machine, although it did sell some brand new folding Coronas some time later.

Above: Alpha and Omega, of sorts. The very first manufactured variant of the Harris Visible, as used by Sears at its offices and as first offered in the Sears catalog in the Summer of 1912 is seen here at left. Note the solid keytops not unlike those on an Oliver. Just a decade later, after more than one bankruptcy and a name change, the final retail sale of this mechanical design occurred when Smith Typewriter Sales offered the remaining formerly-Rex-owned sales sample (and probably office) machines rebuilt at a discount price as the Smith Visible No. 6, at right.

For more information:

For a complete and detailed Harris / Rex / Demountable history click here.

For a complete Harry A. Smith history click here.