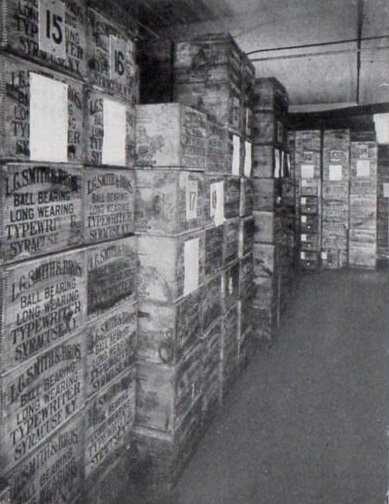

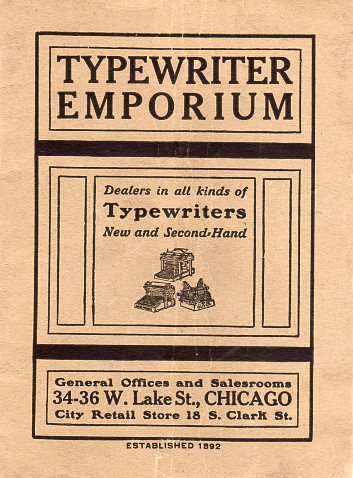

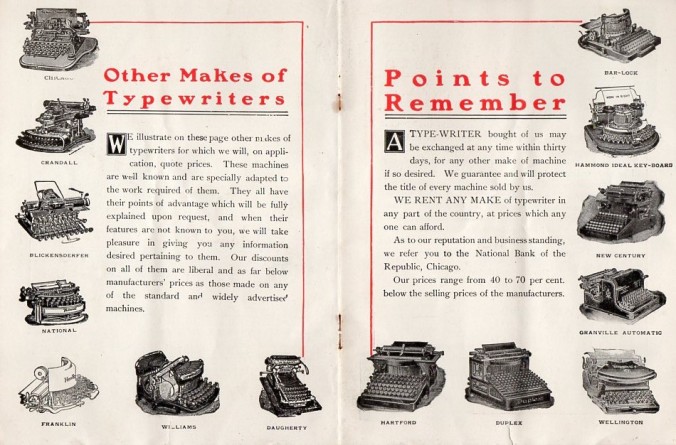

As we have seen, rebuilt and second-hand typewriters were being sold over the period from the early 1890’s through the 1960’s at prices anywhere from roughly 3/4 the price of brand new standard machines all the way down, in some cases, to just over 1/10 the price. That price incentive alone was a serious inducement to buy – but yet there were those who did not wish to buy what they still perceived as an old or used machine. And they did have something to buy, too – because there were always brand-new machines available priced well below the industry average prices for high grade, new machines. This adds yet another angle to our narrative on rebuilt typewriters, and it’s a significant one.

The brand new machines of this “new but less than full price” bracket were most frequently sold by mail order only (which held down overall costs) but a few examples were sold through major catalogues. One of the best was the Harris Visible, sold for a number of years by Sears, Roebuck & Co.

The Harris was first sold at just $39.80 in 1912, but quickly moved up to $44.50; no matter which price though, this definitely was direct competition for rebuilt machines as the Harris was brand new, “shipped direct from the manufacturer” and had a strong warranty.

Perhaps the most significant fact for us today in terms of rebuilt machine history is that Sears was well aware that its machine was in direct competition against rebuilt machines; it proved this by including a long passage about rebuilt machines in its 1913-1914 trade catalog for the Harris. That passage, while heavily biased against second hand and rebuilt typewriters does include many grains of truth and as such is a valuable contemporary official record for us to consider historically. The italics are in the original.

• • • • From the Harris Visible Typewriters trade catalog, page 23:

“A Few Words About Second Hand and ‘Rebuilt’ Typewriters

Before it was possible to secure an efficient new typewriter at a reasonable price, it may have been economy to purchase a second hand or ‘rebuilt’ machine.

But now that the Harris Visible Typewriter is offered at $44.50, we do not believe you will care to purchase any used machine.

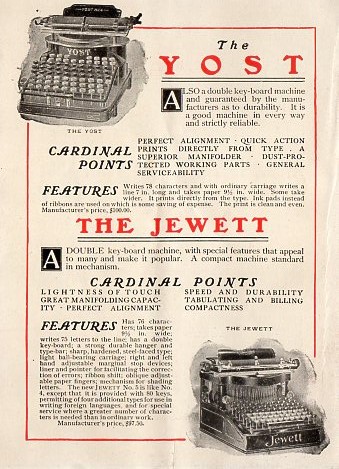

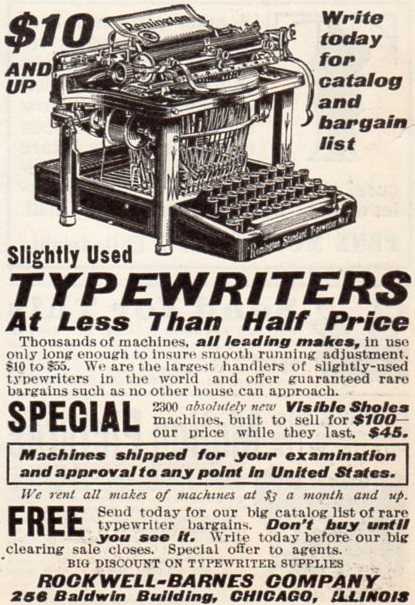

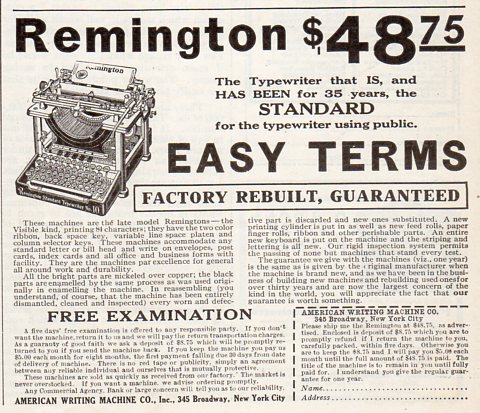

The so-called ‘standard’ typewriters, selling for almost $100.00, are usually sold second hand for $25.00 to $60.00. ‘Rebuilt’ machines net $30.00 to $75.00. The price depends entirely on the length of service and the condition of the machine.

While it is much better to have any typewriter than none, it is still better to have a new machine than one that is second hand or ‘rebuilt.’

Really good typewriters are rarely traded in. In nearly every case when a typewriter is traded in, its greatest usefulness has been pounded out. If it were still efficient, it would not be traded; or if traded and really rebuilt, would command almost the price of a new machine.

Regarding ‘rebuilt’ typewriters – the name is misleading. Very few are actually rebuilt and these sell for $50.00 to $75.00. The others, which sell for $30.00 to $50.00 are old machines, which have been cleaned, polished and ‘tuned up a bit.’ Very few, if any, of the worn parts are replaced with new parts, and even such replacements do not add strength to the parts that remain and which are all more or less worn.

When considering the purchase of any second hand or ‘rebuilt’ machine, remember that you can secure a brand new Harris Visible Typewriter for $44.50.

If you are offered a used machine for even as low as $25.00, remember you can secure a new Harris of the latest type with up to date improvements for only $20.00 more. And remember that the Harris is guaranteed and backed by Sears, Roebuck and Co., one of the largest merchandising institutions in the world. You take no risk; you are guaranteed perfect satisfaction.

Surely, a feeling of confidence in the firm you buy from is worth considering.

Do not buy any second hand machine unless you know its entire history and are satisfied that it has not been unduly worn or abused. It is possible to make temporary repairs in a worn out typewriter which will cause it to do fairly good work for a short time, but it will not last.

We have endeavored to convince you that there is no economy in paying more than our price for any new standard typewriter on the market. How much less economical is it then to pay more than our price for a ‘rebuilt’ machine, or even a slightly used second hand machine!

Our price, $44.50, is a revelation in the typewriter industry. The Harris is good enough for our use and good enough for anybody. We venture to say that there isn’t $5.00 difference in manufacturing cost between the Harris and any of the most expensive typewriters made. Yet there is a difference of about $50.00 in the price the purchaser is asked to pay.

Where does this difference come in? What causes it? You should answer this question before buying.

• • •

The passage above has a number of central themes which I have explored, and will continue to explore, identify and reference on this blog. These themes – things such as trust in the seller, faith in the choice of age and quality versus price – are central to the proposition of both the off-price new machine business and, importantly to us, the rebuilt and second-hand business. Look for much more on these themes in coming posts.